By Daniel Santini and Natalia Viana, Publica

One year had passed since Bahrain became the stage for pro-democracy protests by the majority Shiites against the Sunni monarchy commanded by king Hamad bin-Isa Khalifa. The protesters had been punished by the Bahraini army and neighboring countries. At least 35 people died and hundreds were injured.

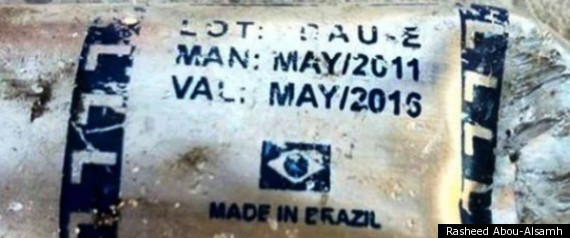

According to the protesters, the Brazilian tear gas used to punish them had also caused the death of babies. “Some people think that the tear gas from Brazil had more chemical substances. There is some kind of ingredient that, in some cases, makes people foam at the mouth and have other symptoms. We are not sure about its composition, but these reactions have been very frightening. It's much worse than American tear gas,” said the human rights activist Zeinab al-Khawaja to Brazil's paper O Globo.

However, little is known about how the gas made by Brazilian non-lethal technology company Condor fell into the hands of troops that punished pro-democracy protesters. The company, located in Nova Iguacu, in Rio de Janeiro, affirms that it doesn’t export to Bahrain, but says that it sells to other countries in the region without specifying which.

According to the protesters, the Brazilian tear gas used to punish them had also caused the death of babies. “Some people think that the tear gas from Brazil had more chemical substances. There is some kind of ingredient that, in some cases, makes people foam at the mouth and have other symptoms. We are not sure about its composition, but these reactions have been very frightening. It's much worse than American tear gas,” said the human rights activist Zeinab al-Khawaja to Brazil's paper O Globo.

However, little is known about how the gas made by Brazilian non-lethal technology company Condor fell into the hands of troops that punished pro-democracy protesters. The company, located in Nova Iguacu, in Rio de Janeiro, affirms that it doesn’t export to Bahrain, but says that it sells to other countries in the region without specifying which.

All arms exports -- whether light arms or not -- are approved by Brazil's Ministry of External Relations and the Ministry of Defense. However, once approved, the government doesn't have much control. The Ministry of External Relations recognizes that it doesn’t have powers to investigate the situation; after the Bahrain scandal, a press officer said that the ministry is merely ‘observing [the development of these occurrences] with interest.'

The responsibility of verifying this information is left up to the company.

“It’s a contract between private parties. It can involve a foreign government, but the company is responsible for its product,” says the press secretary of the Ministry of External Affairs. "The contracts generally prohibit any resale. The company Condor is trying to monitor its product. We are in an ongoing dialogue.”

As Brazil increases its global projection, the government must act to secure its arms industry.

The responsibility of verifying this information is left up to the company.

“It’s a contract between private parties. It can involve a foreign government, but the company is responsible for its product,” says the press secretary of the Ministry of External Affairs. "The contracts generally prohibit any resale. The company Condor is trying to monitor its product. We are in an ongoing dialogue.”

As Brazil increases its global projection, the government must act to secure its arms industry.

Brazil is the fourth biggest global exporter of light arms in the world, ahead of Israel, Austria and Russia, according to the Small Arms Survey, the industry's main study carried out by the IHEID in Geneva. The US is by far the biggest global exporter.

According to data from the Brazilian Ministry of Development, Industry, and Foreign Trade, the value of light arms exports has tripled in the past five years; from $109.6 million in 2005 to $321.6 million in 2010.

Counting just firearms, the quantity is an impressive amount. There were 4,482,874 arms exported between 2005 and 2010, according to a survey carried out by the army at the request of Publica. In other words, 2,456 arms exported a day.

Countries that receive arms produced in Brazil:

Credit: Emídio Pedro. Data from 2009.

Government Support

Within the next few months, a set of measures put forth by the Brazilian government to strengthen the national arms industry will come into force. The measures establish a special taxation regimen with incentives and guarantees on exports. The new law follows the national defense strategypublished in 2008, which establishes industry growth as a goal with incentives for exportation. "The state will help secure foreign clients for the national defense material industry," the strategy says, which forecasts special credit lines from the Brazilian Development Bank.

The Ministry of Defense stated, "We have made gestures to agencies that promote industry growth ... with the intention of making funding available for companies framed in the defense industry."

The Brazilian Development Bank noted that between 2009 and 2011, it made loans worth 71 million reais (about 40 million US dollars) to companies in the sector, and the Brazilian Export and Investment Promotion Agency APEX also took action to "increase exports of defense and security materials and the number of exporting companies," including Brazilian firms in international trade shows such as the Latin America Defense & Security fair.

With this support, the companies are expanding to new markets, primarily in Africa and Asia. As in the case of the company Condor, the tear-gas producer that refused to divulge which countries it deals with, little is known about the destination of arms made in Brazil, and there is no public debate surrounding the issue. In this industry, the norm is a lack of transparency.

The data that indicate an expansion of sales are unavailable, even for the Brazilian Ministry of Defense.

When Publica requested data about the production of arms in Brazil, the ministry told us that they "don't have the means" to respond. "The Ministry of Defense controls production, but doesn't know,a priori, the size of orders placed," their note said. To clarify, the ministry added: "The Ministry of Defense incentivizes the strengthening of the national defense industry, and not an increase of national arms production."

The technical director of the Brazilian Defense and Security Industry Association (ABIMDE), Armando Lemmas, affirms that a survey of the number of arms produced in Brazil doesn't exist.

"Nobody knows the magnitude of national production. We look for fiscal incentives to benefit the manufacturers, but without exact numbers there is nothing to discuss with the Ministry of Finance. We don't know how much is produced, how many people work in the sector, how much money is moved. I don't know, the ex-minister doesn't know, nobody knows. The companies are reluctant to reveal this data."

Lack Of Transparency: National And International Concern

No official estimate about the production of light arms in Brazil exists. The industry doesn't release information about how much it produces and there isn't a government database.

When it comes to international commerce, there is even less transparency.

Publica sought information from the army, which provides general data, but it didn't want to provide details.

Since October 2010, a department (SGEPRODE) that monitors international sales has existed in Brazil. However, the data was never made available to the public.

In the days following the scandal in Bahrain, it came to light in the media that the Ministry of Defense had a bill for a public databank about acquisitions and sales.

However, when contacted by Publica, the ministry vehemently denied any such plan.

"The ministry of defense doesn't know about the legislation cited in the press," it said in a note. "A new law establishes a national registry of the companies, but the way in which the data will be publicized has not yet been defined."

The IHEID in Geneva has a 'barometer' for transparency to assess information provided by big global actors in the light arms market. Brazil never does very well. Since 2011, it has had one of the worst assessments among the principal exporters, only just losing to Russia and China.

In the last study from 2011, Brazil ranked 38th on a list of 50 countries.

Beyond that, the institution says, there is evidence that Brazil "systematically" registers exports of revolvers and pistols erroneously, which generates confusion.

"The assumption is that Brazil wants to keep some secrets, it's keeping information confidential and doing that would benefit its companies. But the consequences are that we know less than what we should about what Brazil is doing," said Nicholas Marsh from the Norwegian Initiative on Small Arms Transfers.

As no legislation or international organization that monitors this commerce exists, there isn't a collection of global data, and no country is required to report to anyone. The data from the UN Register are sent voluntarily.

"This means that there are big fluxes of arms occurring in the world, and nobody knows about it. As a result, the arms end up going to places where they shouldn't be," says Nicholas Marsh. "The worst part is that arms last a long time. If taken care of, a revolver can last 100 years. In Libya, in the beginning of the conflicts, there were people carrying arms from the Second World War."

Exporter

The destination of half of Brazilian revolvers, pistols, and fusils is the United States, the biggest importer of light arms in the world.

The Brazilian arms, particularly those from the companies Taurus and Imbel, are sold to the FBI and to common citizens.

But exports to the US are decreasing, and as a result the manufacturers are looking for new markets.

"The American market continues to be stable, with predicted stability for the next 3 years. The global market, primarily in Africa, is growing; in Asia, too. And we are opening a bigger market," said Jorge Py Velloso, vice president of Taurus, the biggest arms manufacturer in Brazil.

The negotiations surrounding the export of arms to the countries considered priorities for the Brazilian industry count on direct support from the government and the diplomatic structure of the country.

On July 31, 2009, for example, at the invitation of minister of the Ministry of Development, Industry and Foreign Trade, Miguel Jorge, a committee lead by Ghana's military delegation visited São Paulo to negotiate with arms vendors.

The one to receive Ghana's Minister of Defense, general J.H. Smith, and other representatives of the African nation's armed forces, was the official of the chancellery of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Leandro Napolitano Diaz. The committee traveled on one of Brazil's Air Force aircraft.

Publica tried to listen to the directors of the company Taurus about the politics of expansion of arms to Africa, but were refused access.

Surveys done by the Norwegian Initiative on Small Arms Transfers note that, between 1999 and 2009, Brazil sold arms to South Africa, Algeria, Angola, Egypt, Botswana, Burkina Faso, the Ivory Coast, Ghana, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritania, Morocco, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Pakistan, The Democratic Republic Of The Congo, Senegal, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

According to data from the Ministry of Development, Industry and Foreign Trade, Brazil exported to countries such as Trinidad and Tobago, a country considered an arms- and drug-trafficking point in the Caribbean. In the past year, a state of emergency and an 11 pm curfew were decreed because of gang violence. Brazil exported $4.1 million in arms to the country in 2010.

Another importer country that commands attention is the Philippines, where confrontations between the army and Muslim rebels have reached thousands of civilians, especially in the south of the country. Brazil exported $3.8 million in arms in 2010 and $7.5 million in 2011.

The ministry did not supply data about the types of arms sold, financial clients or the companies involved. Each sale of arms has to be approved by the Ministry of Defense and the Ministry of External Affairs. However, the ministries denied to disclose how many licenses were issued and how many were denied. "That information is not available for the public, as part of the executed contracts is protected by a secrecy clause," the press office said.

For Daniel Mack, international coordinator of politics and arms control at the Sou da Paz Institute, the gains have spoken louder than the promise of human rights and civil protections.

"It begs the question: Where will these arms be sold, given the history of our country of not stopping the sale of arms to dictators or repressors? The position that is always repeated and established by the Federal Constitution is to focus on the theme of human rights in our foreign policy, but many times it remains at the mercy of commercial interests of an industry that adds little economically to the country," said Mack.

Arms Buyers Look Increasingly Toward Brazil, American Diplomat Says

The Brazilian government's procedures to free up exports of arms were criticized internally by the American diplomatic mission, according to documents published by WikiLeaks in 2011.

With the country's arms export incentives, "It is therefore probable that governments and non-government actors seeking access to military technology will increasingly turn to Brazil," wrote diplomat Lisa Kubiski in a communication on June 22, 2009, to the US Department.

"Brazil's current system of export controls, with its emphasis on informal consultations and understanding that all our exporters know what they should do, while sufficient for the present, could become inadequate," Kubiski writes.

Another document written by the US Department of State in February of 2009 reiterated that "the Brazilian system of export controls does not include formal links between agencies, relying instead on a 'gentlemen's agreement.'"

The document describes a frustrating visit of a US delegation to Brazil. The objective of their visit was to discuss American rules surrounding exports and imports of defense materials. The committee was not received by Ministry of Defense officials, the Secretariat of the Federal Revenue, nor the federal police.

No International Treaty

The politics of exports expansion in Africa is viewed with concern by international analysts since there is no international agency to regulate global small arms trade. There are only a few treaties and accords, such as the 2000 Protocol against the Illicit Manufacturing of and Trafficking in Firearms.

"To be honest, there are a lot more regulations on the export of corn, cars or any other product, than on arms," said Nicholas Marsh from the Norwegian Initiative on Small Arms Transfers. "Everything has to be registered with the WTO. Commerce is well-regulated. Meanwhile, arms commerce has always been excluded from international treaties."

As a result, since 2006, there is a WTO negotiation about establishing an international treaty to regulate the international commerce of conventional arms, whether heavy or light. Nuclear arms or high-lethality arms, such as clusterbombs, would be treated specifically.

At the time, the negotiations for the Arms Trade Treaty were supported by 153 countries -- including Brazil -- but were rejected by the US, the world's biggest arms exporter. Although the Obama administration had supported the initiative, the majority of US senators were opposed, which resulted in an enormous international impasse.

Such an idea also came up against fierce resistance from arms industry representatives in Brazil.

"You are not going to have global organizations taking care of the market. Each nation is sovereign. Its people deserve respect and have the right to self-determination. Whether they have a bloody dictator or not, the people deserve it," said Jairo Candido, president of Com Defesa, a group from the Federation of Industries of São Paulo (FIESP) that lobbies for the sector.

Daniel Santini is a reporter and an international journalism specialist at the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo (PUC-SP).

Natalia Viana is a Brazilian journalist and director of the investigative nonprofit Publica, whose journalism you can support here.

Original version translated from Portuguese by Clare Richardson.